Chapter One

The rectangular patch of gravel in front of the Admiralty had been criss-crossed countless times since the outbreak of hostilities. It is entirely possible that the retired petty-officer doorman paid little attention to the guest who arrived on 21 April 1915. There were, after all, more important matters for a retired petty-officer doorman to consider; not least the recent departure from the Admiralty of the two dynamic but headstrong individuals who had run the place. Namely, the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and the First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher. They had clashed bitterly over the military fiasco of the Gallipoli campaign. Both were great men; both had fallen because of Churchill’s plan to cut short the War with an invasion of western Turkey.

The visitor was tanned and fit and wore civilian clothes, but otherwise there was nothing remarkable about him. His profession sounded glamorous, however. He was a big-game hunter from Africa and he had an appointment to see the new First Sea Lord, Sir Henry Jackson.

The story the hunter told would set in train some of the strangest events of the First World War. Their conclusion would make famous—for a while, at least—the navy’s most quixotic character since the days of the privateers. Like the hand-made cigarettes he commissioned, his personality was a particular mixture: one that involved as much cowardice as heroism, as much self-regard as self-belief.

This individual’s name—inscribed in pale blue on those hand-made cigarettes—was Geoffrey Spicer-Simson and he held the rank of Lieutenant Commander. He was based in the Admiralty when the hunter paid his visit. The doorman would have known this, because the doormen of Whitehall know everything about the workings of government—especially in wartime, the only time when the Whitehall machine works properly. He would have known that Spicer-Simson sat in no great splendour in a barely furnished office somewhere high up in the building.

High up geographically, that is, because Spicer-Simson was actually in disgrace. And there was a good reason—several good reasons, in fact—why a trained naval commander had spent the first eight months of the War in a dusty office containing two chairs, two desks piled with papers and little else, except a stone fireplace without a fire.

Born in Tasmania in 1876, Geoffrey Basil Spicer-Simson was one of five children. Formerly in the merchant navy, their father Frederick Simson was a dealer in gold sovereigns in India who eventually settled in Le Havre, France, at the age of thirty-one. There he met eighteen-year-old Dora Spicer, daughter of a visiting English clergyman,* and on marrying changed his name to Spicer-Simson. In 1874 they moved to Tasmania, having some family there, and ran a sheep farm for five years. Dora didn’t care for the colonial life, however, and in 1879 they returned to France. The children were sent to schools in England. The eldest, Theodore, became an artist, moving between France and the United States. The youngest, Noel, eventually joined the British army.

Geoffrey Spicer-Simson entered the Royal Navy at the age of fourteen, embarking on what for a considerable time would be a disastrous career. This was partly due to the eccentricities of his character. Boastful and vain-glorious, by the time war was declared he was well known throughout the officer corps. They generally avoided him. One reason for this was that he took every opportunity to show off his arms and upper torso, which were heavily tattooed with depictions of snakes and butterflies. He liked to brag, too, about his individual bravery in many dangerous adventures. Recounted with a distant, rhapsodic look, most of these tales were lies.

An expert on every subject (even in the presence of genuine experts), Spicer also enjoyed telling jokes (nobody laughed at them) and singing (he was invariably off-key). It is not surprising that his fellow officers thought of him as at best peculiar, at worst downright dangerous. It didn’t help that he spoke in a curious manner. Nor that he tended to swagger and throw his weight around. In his groundbreaking history The Great War in Africa (1987), Byron Farwell describes Spicer as “a large, muscular, round-shouldered man with thin, close-cropped hair, a Vandyke beard, and light grey eyes, he affected a nasal drawl . . . He indulged in a proclivity for browbeating waiters and others serving on lower rungs of life than his own.”

Spicer had always wanted to be a hero. After joining the training ship Britannia in 1890 as a cadet, he advanced some way through the ranks, serving in the Gambia and on the China Station, where he made the first hydrographic survey of the Yangtse River. But a series of bumbling errors and catastrophic misjudgements had left him stuck in the naval hierarchy, the oldest lieutenant commander in the navy.

There was, for example, that time during the Channel manoeuvres of 1905 when he suggested it would be a good idea for two destroyers to drag a line strung from one to the other in a periscope-hunting exercise. He nearly sank a submarine. Or there was the time when, in an exercise intended to test the defences of Portsmouth Harbour, he drove his ship onto a nearby beach. He was court-martialled for that.

He was also court-martialled for sinking a liberty boat in a collision, after smashing his destroyer into it. Someone was killed. The incident was reported in the local papers. Lieutenant Commander Spicer-Simson had something of a reputation for disaster.

In August 1914, at the start of the War, Spicer was put in charge of a coastal flotilla consisting of two gunboats and six boarding tugs operating out of Ramsgate. He felt confident enough of the anchorage of his gunboats to come onshore and entertain his wife and some lady friends in a hotel. He could see HMS Niger, one of the ships in question, well enough from the window, could he not?

Fate answered this question with a resounding Yes.

Yes, from the window of the hotel bar Spicer could see Niger as the Germans torpedoed her. He could watch her sink, too, in just twenty minutes. And going down with her, he could see his hopes of advancement to the highest echelon of the navy disappear beneath the waves.

Such was the state of Spicer’s fortunes on 21 April 1915 when a big-game hunter called John Lee arrived at the Admiralty with an appointment to see the new First Sea Lord, Sir Henry Jackson. Lee had great experience of Lake Tanganyika. He also had a scheme to bring it under British control. Britain had no ships on the lake and it was not an area Sir Henry knew anything about, so he was happy to listen to Lee’s plan and called for a map.

How did the War stand in April 1915 on the “forgotten front”? The conflict on the plains, lakes and mountains of Central and East Africa had almost slipped from the mind of the British authorities. On a wooden chart table at the offices of the First Sea Lord at Admiralty House, Whitehall, Lee showed Sir Henry the lie of the land . . .

Here was German East Africa, comprising the present territory of Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. Here were Kenya and Uganda, under British control. So too were the Rhodesias Northern and Southern (now Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively). Further down was South Africa, which was British—though some of the Boers with whom Britain had fought a war between 1899 and 1902 could not be trusted. The South Africans had invaded German South West Africa (now Namibia) at the start of the War. Superior in numbers, by September 1914 the British South Africans had more or less overrun the South-west German territory, though a pro-German rebellion by Boer officers rumbled on until February 1915.

The Germans had more success in East Africa, mainly thanks to their force of Schütztruppen. These highly trained units of German officers and African askaris respected their commander, a military genius called Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. In November 1914 he had repelled a British landing of troops from India at the northern Tanganyikan port of Tanga. This was “a major setback for British ambitions in east Africa,” as Ross Anderson notes in his 2002 study of the battle—and it left many British guns and other supplies in von Lettow’s hands. Another problem was the continuing existence of a big German cruiser called the Königsberg, which was hidden in the swamps of the Rufiji delta farther south near Dar es Salaam, the capital of German East Africa.

If we compare the German army marching into Belgium at the start of the War with the African experience a year or so later, we get a sense of how utterly different were the two theatres of conflict. Here is journalist Richard Harding Davis describing the Germans entering Brussels, mesmerised by their massed grey uniforms:

It is a grey-green . . . the grey of the hour just before daybreak, the grey of unpolished steel, of mist among green trees. I saw it first in the Grande Place in front of the Hôtel de Ville. It was impossible to tell if in that noble square there was a regiment or a brigade. You saw only a fog that melted into the stones, blended with the ancient house fronts, that shifted and drifted, but left nothing at which you could point.

It was, Davis adds, “typical of the German staff striving for efficiency to leave nothing to chance.”

In Africa, by contrast, von Lettow’s Schütztruppen—cut off by British naval power from German supply lines—quickly became a raggedy, make-do outfit that depended on chance and thrived on opportunism. Motor fuel was improvised from cocoa; quinine was brewed from the barks of trees; ammunition was captured from the British. Hippopotamus were shot for their meat and fat, the latter being used to make candles and soap. As Hew Strachan points out (in The First World War, 2001), the most important difference between the two theatres was that the individual was not tyrannised, as he was on the western front, by the industrialisation of warfare.

Yet if there was a great material and psychological difference between von Lettow’s rag-tag force and the Prussian Junker—the “road-hog of Europe” as Lloyd George once described it—they shared the same philosophy, the same sense of belonging to a military brotherhood. It was an emotional business, as the memoirs of one German captain reveal. Describing the moment when the German army crossed the Rhine into Belgium, Walter Bloem wondered: “Was it real or was I living in a dream, in a fairy-tale, in some heroic epic of the past?”

No stranger himself to such feelings of fraternal heroism, von Lettow had something else, too. Nous, you might call it: that quality of cunning which brings Odysseus home to Ithaca and saves the fox from the hounds. Like Odysseus, von Lettow did not follow a straight line. He made the British chase him all over Central and East Africa.

Nor would Spicer-Simson, on the great journey that was to come, follow straight lines. But he wanted to. He strayed from the path through error, showed nous not by design but by mistake. It was his dream, his hope, to be an epic hero. What kind of hero he turned out to be instead—well, that is what this book hopes to show. It is not necessarily the story of a career in decline, because there was nowhere left for him to fall. Much later, his friend Dr. Hanschell, who would accompany him to Africa, recalled Spicer’s dilapidated office in the Intelligence Division of the Admiralty office:

Light filtered through the upper part of a dusty window and showed its meagre furnishings—a filing cabinet, an empty fire grate with a bare yellow mantelpiece, and above it a signed photograph of His Majesty the King in a heavy frame. There were two swivel armchairs, and two desks piled high with papers—it appeared that it was only the room, and not Spicer, that was in the Intelligence Division, for the papers dealt with the transfer of Merchant Marine Officers and Seamen to the Royal Naval Reserve. A cracked teapot on a tray with two empty cups was perched on a corner of the mantelpiece.

To Spicer at that time it must have seemed that the First World War was his last chance to make good and win the laurels he longed for. His sculptor brother Theodore Spicer-Simson was famous for his portrait medallions of celebrities such as the conductor Toscanini and the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Why shouldn’t he have his share of glory too? Why was he now stuck in a desk job in Whitehall and not out on the high seas in the thick of the action?

John Lee, the big-game hunter, explained to the Admiral that the Germans had two steamers under military orders on Lake Tanganyika: the 60-ton Hedwig von Wissmann and the 45-ton Kingani. There were two petrol motor boats as well. One of them, the Peter, had been donated to the German forces by the Gesellschaft für Schlaftkrankheitsbekämpfung (The Society for the Fight against Sleeping Sickness). The Germans also had a fleet of dhows and a number of “Boston whalers”—wooden boats based on an American design that were originally brought to East Africa in the early 1900s.

Lee had also heard vague talk of another steamer (his spies among the Holo-holo tribe had definitely said the Germans had three big boats), but he made no particular mention of it to Sir Henry. Nor did the Belgian army intelligence report which Sir Henry commissioned as a follow-up. This omission, as it turned out, would have devastating consequences.

Lee’s scheme to attack the German steamers was simple in conception, but difficult in practice: if two British motor boats could be sent to South Africa, up the railway to the Belgian Congo, and dragged through mountains and bush to the lake, they could then sink or disable the Hedwig and the Kingani. Taking control of Lake Tanganyika in this manner would allow Belgian forces from the Congo and British forces from Kenya and Northern Rhodesia to drive the Germans back to the eastern seaboard. That was the idea, anyway.

In one of the Admiralty’s beautifully appointed rooms—all oak panels and heavy chairs and paintings of Drake and Franklin—naval experts quizzed Lee on why it was not better to take much bigger boats. The Germans had taken out the Hedwig in sections in 1900, they told him. Why could we not do the same?

The hunter explained that African spies told the Germans everything. If they heard that a big ship was being assembled on the lakeshore they would land and try to damage or destroy it, just as they had done with the Belgian ship Alexandre del Commune. This, and associated problems with the supply of parts, was why the Belgians were keeping back their biggest steamer, the Baron Dhanis, which remained in pieces at a railhead in the Congolese interior.

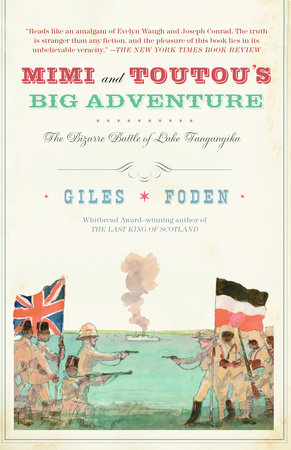

Copyright © 2005 by Giles Foden. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.