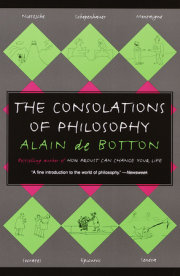

from Part One: Wisdom without Doctrine

1.

The most boring and unproductive question one can ask of any religion is whether or not it is true – in terms of being handed down from heaven to the sound of trumpets and supernaturally governed by prophets and celestial beings.

To save time, and at the risk of losing readers painfully early on in this project, let us bluntly state that of course no religions are true in any God-given sense. This is a book for people who are unable to believe in miracles, spirits or tales of burning shrubbery, and have no deep interest in the exploits of unusual men and women like the thirteenth-century saint Agnes of Montepulciano, who was said to be able to levitate two feet off the ground while praying and to bring children back from the dead – and who, at the end of her life (supposedly), ascended to heaven from southern Tuscany on the back of an angel.

2.

Attempting to prove the non-existence of God can be an entertaining activity for atheists. Tough-minded critics of religion have found much pleasure in laying bare the idiocy of believers in remorseless detail, finishing only when they felt they had shown up their enemies as thorough-going simpletons or maniacs.

Though this exercise has its satisfactions, the real issue is not whether God exists or not, but where to take the argument once one decides that he evidently doesn’t. The premise of this book is that it must be possible to remain a committed atheist and nevertheless find religions sporadically useful, interesting and consoling – and be curious as to the possibilities of importing certain of their ideas and practices into the secular realm.

One can be left cold by the doctrines of the Christian Trinity and the Buddhist Eightfold Path and yet at the same time be interested in the ways in which religions deliver sermons, promote morality, engender a spirit of community, make use of art and architecture, inspire travels, train minds and encourage gratitude at the beauty of spring. In a world beset by fundamentalists of both believing and secular varieties, it must be possible to balance a rejection of religious faith with a selective reverence for religious rituals and concepts.

It is when we stop believing that religions have been handed down from above or else that they are entirely daft that matters become more interesting. We can then recognize that we invented religions to serve two central needs which continue to this day and which secular society has not been able to solve with any particular skill: first, the need to live together in communities in harmony, despite our deeply rooted selfish and violent impulses. And second, the need to cope with terrifying degrees of pain which arise from our vulnerability to professional failure, to troubled relationships, to the death of loved ones and to our decay and demise. God may be dead, but the urgent issues which impelled us to make him up still stir and demand resolutions which do not go away when we have been nudged to perceive some scientific inaccuracies in the tale of the seven loaves and fishes.

The error of modern atheism has been to overlook how many aspects of the faiths remain relevant even after their central tenets have been dismissed. Once we cease to feel that we must either prostrate ourselves before them or denigrate them, we are free to discover religions as repositories of a myriad ingenious concepts with which we can try to assuage a few of the most persistent and unattended ills of secular life.

Copyright © 2012 by Alain De Botton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.