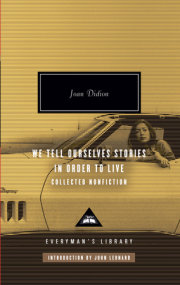

Chapter 1 1.

Life changes fast.Life changes in the instant.You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.The question of self-pity.Those were the first words I wrote after it happened. The computer dating on the Microsoft Word file (“Notes on change.doc”) reads “May 20, 2004, 11:11 p.m.,” but that would have been a case of my opening the file and reflexively pressing save when I closed it. I had made no changes to that file in May. I had made no changes to that file since I wrote the words, in January 2004, a day or two or three after the fact.For a long time I wrote nothing else.

Life changes in the instant.The ordinary instant.At some point, in the interest of remembering what seemed most striking about what had happened, I considered adding those words, “the ordinary instant.” I saw immediately that there would be no need to add the word “ordinary,” because there would be no forgetting it: the word never left my mind. It was in fact the ordinary nature of everything preceding the event that prevented me from truly believing it had happened, absorbing it, incorporating it, getting past it. I recognize now that there was nothing unusual in this: confronted with sudden disaster we all focus on how unremarkable the circumstances were in which the unthinkable occurred, the clear blue sky from which the plane fell, the routine errand that ended on the shoulder with the car in flames, the swings where the children were playing as usual when the rattlesnake struck from the ivy. “He was on his way home from work—happy, successful, healthy—and then, gone,” I read in the account of a psychiatric nurse whose husband was killed in a highway accident. In 1966 I happened to interview many people who had been living in Honolulu on the morning of December 7, 1941; without exception, these people began their accounts of Pearl Harbor by telling me what an “ordinary Sunday morning” it had been. “It was just an ordinary beautiful September day,” people still say when asked to describe the morning in New York when American Airlines 11 and United Airlines 175 got flown into the World Trade towers. Even the report of the 9/11 Commission opened on this insistently premonitory and yet still dumbstruck narrative note: “Tuesday, September 11, 2001, dawned temperate and nearly cloudless in the eastern United States.”“And then—gone.”

In the midst of life we are in death, Episcopalians say at the graveside. Later I realized that I must have repeated the details of what happened to everyone who came to the house in those first weeks, all those friends and relatives who brought food and made drinks and laid out plates on the dining room table for however many people were around at lunch or dinner time, all those who picked up the plates and froze the leftovers and ran the dishwasher and filled our (I could not yet think

my) otherwise empty house even after I had gone into the bedroom (our bedroom, the one in which there still lay on a sofa a faded terrycloth XL robe bought in the 1970s at Richard Carroll in Beverly Hills) and shut the door. Those moments when I was abruptly overtaken by exhaustion are what I remember most clearly about the first days and weeks. I have no memory of telling anyone the details, but I must have done so, because everyone seemed to know them. At one point I considered the possibility that they had picked up the details of the story from one another, but immediately rejected it: the story they had was in each instance too accurate to have been passed from hand to hand. It had come from me.Another reason I knew that the story had come from me was that no version I heard included the details I could not yet face, for example the blood on the living room floor that stayed there until José came in the next morning and cleaned it up.José. Who was part of our household. Who was supposed to be flying to Las Vegas later that day, December 31, but never went. José was crying that morning as he cleaned up the blood. When I first told him what had happened he had not understood. Clearly I was not the ideal teller of this story, something about my version had been at once too offhand and too elliptical, something in my tone had failed to convey the central fact in the situation (I would encounter the same failure later when I had to tell Quintana), but by the time José saw the blood he understood.I had picked up the abandoned syringes and ECG electrodes before he came in that morning but I could not face the blood.In outline.It is now, as I begin to write this, the afternoon of October 4, 2004.Nine months and five days ago, at approximately nine o’clock on the evening of December 30, 2003, my husband, John Gregory Dunne, appeared to (or did) experience, at the table where he and I had just sat down to dinner in the living room of our apartment in New York, a sudden massive coronary event that caused his death. Our only child, Quintana, had been for the previous five nights unconscious in an intensive care unit at Beth Israel Medical Center’s Singer Division, at that time a hospital on East End Avenue (it closed in August 2004) more commonly known as “Beth Israel North” or “the old Doctors’ Hospital,” where what had seemed a case of December flu sufficiently severe to take her to an emergency room on Christmas morning had exploded into pneumonia and septic shock. This is my attempt to make sense of the period that followed, weeks and then months that cut loose any fixed idea I had ever had about death, about illness, about probability and luck, about good fortune and bad, about marriage and children and memory, about grief, about the ways in which people do and do not deal with the fact that life ends, about the shallowness of sanity, about life itself. I have been a writer my entire life. As a writer, even as a child, long before what I wrote began to be published, I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs, a technique for withholding whatever it was I thought or believed behind an increasingly impenetrable polish. The way I write is who I am, or have become, yet this is a case in which I wish I had instead of words and their rhythms a cutting room, equipped with an Avid, a digital editing system on which I could touch a key and collapse the sequence of time, show you simultaneously all the frames of memory that come to me now, let you pick the takes, the marginally different expressions, the variant readings of the same lines. This is a case in which I need more than words to find the meaning. This is a case in which I need whatever it is I think or believe to be penetrable, if only for myself. 2.December 30, 2003, a Tuesday.We had seen Quintana in the sixth-floor ICU at Beth Israel North.We had come home.We had discussed whether to go out for dinner or eat in.I said I would build a fire, we could eat in.I built the fire, I started dinner, I asked John if he wanted a drink.I got him a Scotch and gave it to him in the living room, where he was reading in the chair by the fire where he habitually sat.The book he was reading was by David Fromkin, a bound galley of

Europe’s Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?I finished getting dinner, I set the table in the living room where, when we were home alone, we could eat within sight of the fire. I find myself stressing the fire because fires were important to us. I grew up in California, John and I lived there together for twenty-four years, in California we heated our houses by building fires. We built fires even on summer evenings, because the fog came in. Fires said we were home, we had drawn the circle, we were safe through the night. I lit the candles. John asked for a second drink before sitting down. I gave it to him. We sat down. My attention was on mixing the salad.John was talking, then he wasn’t.At one point in the seconds or minute before he stopped talking he had asked me if I had used single-malt Scotch for his second drink. I had said no, I used the same Scotch I had used for his first drink. “Good,” he had said. “I don’t know why but I don’t think you should mix them.” At another point in those seconds or that minute he had been talking about why World War One was the critical event from which the entire rest of the twentieth century flowed.I have no idea which subject we were on, the Scotch or World War One, at the instant he stopped talking.I only remember looking up. His left hand was raised and he was slumped motionless. At first I thought he was making a failed joke, an attempt to make the difficulty of the day seem manageable.I remember saying

Don’t do that.When he did not respond my first thought was that he had started to eat and choked. I remember trying to lift him far enough from the back of the chair to give him the Heimlich. I remember the sense of his weight as he fell forward, first against the table, then to the floor. In the kitchen by the telephone I had taped a card with the New York–Presbyterian ambulance numbers. I had not taped the numbers by the telephone because I anticipated a moment like this. I had taped the numbers by the telephone in case someone in the building needed an ambulance.Someone else.I called one of the numbers. A dispatcher asked if he was breathing. I said

Just come. When the paramedics came I tried to tell them what had happened but before I could finish they had transformed the part of the living room where John lay into an emergency department. One of them (there were three, maybe four, even an hour later I could not have said) was talking to the hospital about the electrocardiogram they seemed already to be transmitting. Another was opening the first or second of what would be many syringes for injection. (Epinephrine? Lidocaine? Procainamide? The names came to mind but I had no idea from where.) I remember saying that he might have choked. This was dismissed with a finger swipe: the airway was clear. They seemed now to be using defibrillating paddles, an attempt to restore a rhythm. They got something that could have been a normal heartbeat (or I thought they did, we had all been silent, there was a sharp jump), then lost it, and started again.“He’s still fibbing,” I remember the one on the telephone saying.“

V-fibbing,” John’s cardiologist said the next morning when he called from Nantucket. “They would have said ‘

V-fibbing.’ V for ventricular.”Maybe they said “V-fibbing” and maybe they did not. Atrial fibrillation did not immediately or necessarily cause cardiac arrest. Ventricular did. Maybe ventricular was the given.I remember trying to straighten out in my mind what would happen next. Since there was an ambulance crew in the living room, the next logical step would be going to the hospital. It occurred to me that the crew could decide very suddenly to go to the hospital and I would not be ready. I would not have in hand what I needed to take. I would waste time, get left behind. I found my handbag and a set of keys and a summary John’s doctor had made of his medical history. When I got back to the living room the paramedics were watching the computer monitor they had set up on the floor. I could not see the monitor so I watched their faces. I remember one glancing at the others. When the decision was made to move it happened very fast. I followed them to the elevator and asked if I could go with them. They said they were taking the gurney down first, I could go in the second ambulance. One of them waited with me for the elevator to come back up. By the time he and I got into the second ambulance the ambulance carrying the gurney was pulling away from the front of the building. The distance from our building to the part of New York–Presbyterian that used to be New York Hospital is six crosstown blocks. I have no memory of sirens. I have no memory of traffic. When we arrived at the emergency entrance to the hospital the gurney was already disappearing into the building. A man was waiting in the driveway. Everyone else in sight was wearing scrubs. He was not. “Is this the wife,” he said to the driver, then turned to me. “I’m your social worker,” he said, and I guess that is when I must have known.I opened the door and I seen the man in the dress greens and I knew. I immediately knew.” This was what the mother of a nineteen-year-old killed by a bomb in Kirkuk said on an HBO documentary quoted by Bob Herbert in

The New York Times on the morning of November 12, 2004. “But I thought that if, as long as I didn’t let him in, he couldn’t tell me. And then it—none of that would’ve happened. So he kept saying, ‘Ma’am, I need to come in.’ And I kept telling him, ‘I’m sorry, but you can’t come in.’ ”When I read this at breakfast almost eleven months after the night with the ambulance and the social worker I recognized the thinking as my own.Inside the emergency room I could see the gurney being pushed into a cubicle, propelled by more people in scrubs. Someone told me to wait in the reception area. I did. There was a line for admittance paperwork. Waiting in the line seemed the constructive thing to do. Waiting in the line said that there was still time to deal with this, I had copies of the insurance cards in my handbag, this was not a hospital I had ever negotiated—New York Hospital was the Cornell part of New York–Presbyterian, the part I knew was the Columbia part, Columbia-Presbyterian, at 168th and Broadway, twenty minutes away at best, too far in this kind of emergency—but I could make this unfamiliar hospital work, I could be useful, I could arrange the transfer to Columbia-Presbyterian once he was stabilized. I was fixed on the details of this imminent transfer to Columbia (he would need a bed with telemetry, eventually I could also get Quintana transferred to Columbia, the night she was admitted to Beth Israel North I had written on a card the beeper numbers of several Columbia doctors, one or another of them could make all this happen) when the social worker reappeared and guided me from the paperwork line into an empty room off the reception area. “You can wait here,” he said. I waited. The room was cold, or I was. I wondered how much time had passed between the time I called the ambulance and the arrival of the paramedics. It had seemed no time at all (

a mote in the eye of God was the phrase that came to me in the room off the reception area) but it must have been at the minimum several minutes.

Copyright © 2005 by Joan Didion. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.