PART ONE

Poetry

Introduction

In 1781 Thomas Jefferson completed the first draft of what would come to be known as Notes on the State of Virginia. At inception, however, it was a collection of responses to a number of queries from a French aristocrat, Francois, Marquis de Barbe-Marbois, who served as secretary of the French legation to the United States between 1779 and 1785. Marbois' queries were wide-ranging, arising out of the science of the time, which had not yet coalesced into discrete disciplines, but instead mingled geology, geography, zoology, physiology, psychology, philosophy, biology, and botany under the rubric of "natural history," a proto-discipline that depended less on systematic investigation, and much less on experimentation, than on personal observation. Jefferson's responses, therefore, though wide-ranging and thorough, were essentially opinions allegedly supported by reason.

Jefferson gave a fairly complete and accurate description of the geography, geology, flora, fauna, population, and social organization of Virginia a dispassionate, academic expression by a well-versed Man of Reason, which Jefferson purportedly was. But in the midst of his response to one query, Jefferson seemed to forget he was a member of the American Philosophical Society and became something altogether more agendaed.

The query read simply: "The administration of justice and description of the laws?"

Jefferson's response began, "The state is divided into counties. In every county are appointed magistrates, called justices of the peace . . ." and continued with a long and tedious summary of Virginia's statutes governing everything from landholding to marriage and naturalization. The discussion became more interesting when Jefferson explained an ongoing revision of the codes intended to remove colonial vestiges, mentioning his own proffered amendment to the revision plan itself: a proposal to emancipate Negro slaves born in Virginia once they had reached majority, at which time, "they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper."

Although this would not have affected the legal status of slavery itself, applied only to blacks born in the future and would have given slave owners the right to work even those blacks for at least ten years, it was clear that this plan would eventually cause a labor shortage. This Jefferson proposed to remedy by sending "vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither."

That all this seemed somewhat byzantine, Jefferson acknowledged in a rhetorical question:

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave?

which he answered with a mordant prediction:

Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.

Jefferson then proceeded to enumerate the "real distinctions" of nature, laying out a series of canards that constitute a systematic codification, not of the laws of Virginia, but of the tropes of American racism. These included:

They secrete less by the kidnies, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour. . . .

They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But this may perhaps proceed from a want of fore-thought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present. . . .

They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. . . .

In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection. To this must be ascribed their disposition to sleep when abstracted from their diversions, and unemployed in labour. An animal whose body is at rest, and who does not reflect, must be disposed to sleep, of course.

In imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.

In music they are more generally gifted than the whites with accurate ears for tune and time, and they have been found capable of imagining a small catch. Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved.

However, the first trope Jefferson articulated was of particular interest:

The first difference that strikes us is that of colour. . . . And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these, flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgement in favor of the whites, declared by their preference for them, as uniformly is the preference of the Oranootan for the black woman over those of his own species.

This was not merely an expression of personal aesthetics an assertion that black is not, in fact, beautiful. The last part of the passage referred to a belief, seriously held by many educated Europeans, that given opportunity, African apes would come down out of the trees and force themselves on African females. Winthrop Jordan, in White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812, explains this belief in psychological terms: "By forging a sexual link between Negroes and apes . . . Englishmen were able to give vent to their feelings that Negroes were a lewd, lascivious, and wanton people." Jefferson altered and extended the belief about the behavior of non-human animals to the behavior of human animals. What makes this curious especially in the context of a discussion of the laws of Virginia is that in discussing marriage elsewhere in his reply, Jefferson makes no mention of the anti-miscegenation laws, although such laws had been part of the Southern criminal codes, including Virginia's, for a hundred years. The existence and form of those laws made it quite clear that fully consensual sexual relationships between blacks of both genders and whites of both genders were so common that they had to be legally discouraged. But Jefferson turned that which was often a mutually consensual, albeit illegal, conjoining of black male and white female into something that was inevitably bestial rape, while making no mention of that other business, of white male masters coupling with black female slaves. It is not clear whether, at the time of this writing, Jefferson himself had engaged in such behavior, but he knew it existed. Yet rather than acknowledge the fact, or even the obvious implication, of the long-standing miscegenation laws, Jefferson chose to extend the European belief and suggest that the Negro male was as rapacious with respect to white females as was the "Oranootan" toward black females.

After listing these and other disparagements, Jefferson modestly summarized:

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind

and stated a conclusion in the form of another rhetorical question:

Will not a lover of natural history then, one who views the gradations of all the races of animals with the eye of philosophy, excuse an effort to keep those in the department of man as distinct as nature has formed them? This unfortunate difference of colour, and perhaps of faculty, is a powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people.

The Notes were published in England in 1797. Three years later, Jefferson was installed as president of the American Philosophical Society, the first scientific body in the nation. Almost simultaneously he was elected vice president of the United States. Three years later, as he was becoming the nation's third president, Jefferson implicitly reiterated this position by publishing an appendix to the Notes. Thus, at the dawn of the nineteenth century, "Query XIV" constituted a public expression of American racial beliefs, articulated by one of the nation's most powerful intellectual authorities and its most powerful political authority.

At the end of the century, the notions expressed in Query XIV were palpable in the American reality. Jefferson's desire to deport American blacks to "such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper" had been one motivation for his constitutionally questionable prosecution of the Louisiana Purchase, which had created much of the trans-Appalachian America celebrated at the Chicago Exposition. His mordant prediction of fatal conflicts between black and white in the South seemed by then to have come terribly true; certainly the terrorism called lynching seemed to fulfill the prophecy of "new provocations." Just who was being provoked was a question answered by Jefferson's conversion of consent to rape, since the justification most often given for lynching was that a black male had brought it on himself by "insulting" a white woman and any sexual contact between black male and white female was assumed to be rape, even if the woman claimed it was consensual. Meanwhile, Jefferson's more general disparagements were used to justify the increasing trend for states to pass laws requiring racial segregation, and the final thrust of his argument, that blacks, being inferior, were unworthy of political equality, justified the "grandfather clauses" and other stratagems being used to deny blacks the right to vote.

Not surprisingly, the arguments employed by blacks to attack disenfranchisement, segregation, and violence focused on the terms laid out in Query XIV. For example, Ida B. Wells's first pamphlet, "Southern Horrors," was not merely an expose of incredible inhumanity, but an argument against a Jeffersonian implication. Many Americans, including many black Americans, accepted that the allegations of rape and attempted rape associated with lynching were true. Wells herself accepted that view, until she was prompted to begin systematic investigation. In "Southern Horrors" she presented documentary evidence beginning with a case from Ohio that the allegations were but a cover story for what was actually terrorism designed to achieve economic and political ends. She made the argument again in "A Red Record," but many still did not get the point; years later, Dunbar's friend, Toledo mayor Brand Whitlock, would object to Dunbar's use of the term "innocent" to refer to lynching victims in "The Haunted Oak."

Opposition to Query XIV also promoted more artistic literary activity, as one of Jefferson's disparagements was

never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of a plain narration. . . . Misery is often the parent of the most affecting touches in poetry. Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry.

Jefferson had gone on to deny the significance of what, in 1781, was a well-known counterexample:

Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic]; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.

Jefferson's disparagement of Boston's Phillis Wheatley was essential to his general argument. Brought to Boston from Africa at the age of about six, she had learned quickly and well and soon produced poems that were so in keeping with the conventions of English poetry that it had been suspected that "the compositions published under her name" had in fact been written by someone else which is to say, someone white. That they had not been was an evaluation made by the most prominent men of Boston, including John Hancock, co-signer, with Jefferson, of the Declaration of Independence. A volume of her verse, Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral, had been published in England in 1773. Marbois, the intended recipient of Jefferson's Notes, was well aware of her. In fact, he had written about Wheatley. His opinion of her work was not particularly favorable, however ("there is imagination poetry and zeal but no correctness nor order nor interest"). Jefferson's assertion that Wheatley's work was "below the dignity of criticism" was not evaluation, but desperation: her career, fairly judged, was evidence that tore his thesis to tatters.

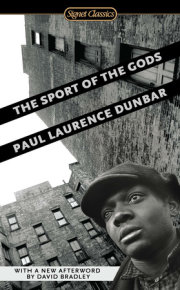

The effect of Jefferson's disparagement was, in some ways, positive, as it encouraged black institutions, especially the churches and the schools, to pay more attention to art, particularly literature, than they might otherwise have. It was, for example, typical that Paul Laurence Dunbar's first public performance was the recitation of his "An Easter Ode" at Eaker Street African Methodist Episcopal Church, when he was about twelve, or that many of his early professional recitations and sales of his poetry collection Oak & Ivy took place under the auspices of church groups. While ministers and parishioners may not have known about Query XIV, they understood that a literary text produced by a black person was not merely an artistic expression, but evidence. The black intelligentsia did know about Query XIV, and they welcomed literary efforts as demonstration that either Jefferson had been wrong about black capability or, if he had been right, he was right no longer.

But this also placed certain expectations on the writers and the texts, specifically, that what was produced be acceptable in the sight of the white critical establishment that the work be above "the dignity of criticism." The result was that literature produced by blacks was viewed in a complicated light. As Winthrop Jordan put it, "From the very first, Negro Literature was chained to the issue of racial equality." This fact has had an ongoing effect not only on black American literature, but on the criticism of black American literature. Certainly it has had an effect on critical statements about Dunbar.

By the time Dunbar appeared at the World's Columbian Exposition, many black writers had produced texts good enough to confound Jefferson. But there were logical problems. The greatest body of black writing was the "slave narratives," many of which had been produced with the assistance of white "editors," which complicated their use as evidence of equality. (It is no accident that the full title of Frederick Douglass's first book was Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself.)

An additional problem was that many of the black writers were of mixed blood. This made it possible to argue as many did that it was this admixture of European blood that enabled them to write. In Europe, this rationalization was used to dismiss the challenge to white cultural superiority presented by the Russian Pushkin and the Frenchman Dumas. In America, it was used to dismiss the challenge to white political supremacy presented by Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Charlotte Forten, F. E. Watkins, and Dunbar's fellow Ohioan Charles W. Chesnutt.

But Dunbar was what in his time was called a "pure black" meaning that his parentage was pure freed slave, with no white master lurking in the woodpile. While the faces of men like Douglass and Booker T. Washington and the young Harvard Ph.D. and Wilberforce professor W.E.B. Du Bois showed clearly the presence of Caucasian genes, Dunbar's complexion was dark, his features negroid.

Copyright © 2005 by Paul Laurence Dunbar. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.