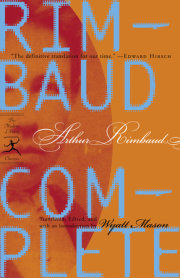

Chapter 1NOTE LEFT IN THE MAILBOX OF GEORGES IZAMBARD

[Charleville; undated, most likely late winter 1870]

If you have, and if you can lend me:

(above all)1: Historical Curiosities, volume one by (I think) Ludovic Lalanne;

2: Bibliographical Curiosities, volume one by same;

3: French Historical Curiosities, by P. Jacob, first series, including the Feast of Fools, the King of the Ribauds, the Francs-Taupins, and Jesters of France,

(And above all). . . and the second series of same.

I'll come by for them tomorrow, around ten or ten-fifteen. -I'll be in your debt. They will be most useful.

Arthur Rimbaud

TO THÉODORE DE BANVILLE

Charleville (Ardennes), May 24, 1870

Cher Maître,

These are the months of love; I'm seventeen, the time of hope and chimeras, as they say, and so, a child blessed by the hand of the Muse (how trivial that must seem), I've set out to express my good thoughts, my hopes, my feelings, the provinces of poets-I call all of this spring.

For if I have decided to send you a few poems-via the hands of Alp. Lemerre, that excellent editor-it is because I love all poets, all the good Parnassians-since the poet is inherently Parnassian-taken with ideal beauty; that is what draws me to you, however naïvely, your relation to Ronsard, a brother of the masters of 1830, a true romantic, a true poet. That is why. Silly, isn't it? But there it is.

In two years, perhaps one, I will have made my way to Paris. -Anch'io, gentlemen of the press, I will be a Parnassian! Something within me . . . wants to break free . . . I swear, Master, to eternally adore the two goddesses, Muse and Liberty.

Try to keep a straight face while reading my poems: You would make me ridiculously happy and hopeful were you, Maître, to see if a little room were found for "Credo in Unam" among the Parnassians . . . I could appear in the final issue of le Parnasse: it would be a Credo for poets! Ambition! Such madness!

Arthur Rimbaud

***

Through blue summer nights I will pass along paths,

Pricked by wheat, trampling short grass:

Dreaming, I will feel coolness underfoot,

Will let breezes bathe my bare head.

Not a word, not a thought:

Boundless love will surge through my soul,

And I will wander far away, a vagabond

In Nature-as happily as with a woman.

April 20, 1870

A.R.

OPHELIA

I

On calm black waters filled with sleeping stars

White Ophelia floats like a lily,

Floating so slowly, bedded in long veils . . .

-Hunting horns rise from the distant forest.

A thousand years without sad Ophelia,

A white ghost on the long black river;

A thousand years of her sweet madness

Murmuring its ballad in the evening breeze.

The wind kisses her breasts, arranges her veils

In a wreath softly cradled by waters;

Shivering willows weep at her shoulder,

Reeds bend over her broad dreaming brow.

Rumpled water lilies sigh around her;

And up in a sleeping alder she sometimes stirs,

A nest from which a tiny shiver of wings escapes:

-A mysterious song falls from golden stars.

II

O pale Ophelia. Beautiful as snow.

You died, child, borne away upon waters.

Winds from high Norwegian mountains

Whispered warnings of liberty's sting;

Because a breath carried strange sounds

To your restless soul, twisting your long hair,

Your heart listened to Nature's song

In grumbling trees and nocturnal sighs,

Because deafening voices of wild seas

Broke your infant breast, too human and too soft;

Because one April morning, a pale, handsome knight,

A poor fool, sat silent at your feet.

Sky. Love. Liberty. What dreams, poor Ophelia.

You melted upon him like snow in flame:

Visions strangled your words

-Fear of the Infinite flared in your eyes.

III

-And the poet says you visit after dark

In starlight, seeking the flowers you gathered,

And that on the water, sleeping in long veils

He saw white Ophelia floating like a lily.

15 May 1870

Arthur Rimbaud

CREDO IN UNAM . . .

The sun, hearth of tenderness and life,

Spills molten love onto a grateful earth,

And, when you're asleep in a valley, you can feel

The earth beneath you, nubile and ripe with blood;

Her huge breast, rising with the soul within,

Is, like god, made of love; like woman, made of flesh;

Heavy with sap and sunlight,

And embryonic swarms.

How it all grows, how it all rises.

-O Venus, O Goddess.

I long for the lost days of youth,

For wanton satyrs and beastly fauns,

Gods who, for love, bit the bark of branches

And kissed blonde Nymphs in water-lily pools.

I long for lost days: when the rosy blood

Of green trees, the water in rivers,

When the world's sap flowed,

Pouring a universe into Pan's veins.

When the green ground breathed beneath his goat's feet;

When his lips, softly kissing his syrinx,

Sent a song of love into the sky;

When, standing on the plain, he heard

Nature respond to his call;

When the silent trees cradled the songbird,

When the earth cradled man, the blue seas

And the beloved beasts-beloved in God.

I long for lost days when great Cybele

In all her boundless beauty was said

To cut across magnificent cities

In a great bronze chariot, both of her breasts

Spilling the pure stream of eternal life

Unto the breach. Mankind suckled

Her blessed breast like a delighted little child.

-Because he was strong, Man was gentle and chaste.

Misery! For now he says: I know everything,

And therefore wanders, eyes closed, ears shut. -And yet,

No more gods! No more gods! Man is King.

Man is God! But Love remains our Faith.

O Cybele! O grandmother of gods and men,

If only man could linger at your breast,

If only he hadn't forsaken immortal Astarte

Who, flower of flesh, odor of oceans,

Once rose from the vast brightness of the blue waves,

Baring a rosy belly snowing foam, goddess

With great black conquering eyes

Who made the nightingale sing in forests

And love in human hearts.

I believe in You! I believe in You! Divine Mother,

Aphrodite of the sea! Oh the way is bitter

Now that another God has yoked us to his cross;

Flesh, Marble, Flower, Venus: I believe in you!

-Man is sad and ugly, sad beneath an enormous sky,

He is clothed for he is no longer chaste,

He has sullied his godly head,

And his Olympian body is stooped

In dirty servitude, an idol in the fire.

Yes, even in death, even as a pale skeleton

He would live on, an insult to his original beauty.

-And the Idol upon whom you lavished your virginity,

In whom you made mere clay divine, Woman,

So that Man might illuminate his poor soul

And slowly climb, in limitless love,

From the earthy prison to the beauty of light-

Woman has forgotten her virtue.

-Such a farce! And now the world snickers

At the sacred name of mother Venus.

If only lost time would return.

-Man is done for, has played his part.

In the light, weary of smashing his idols

He revives, free from his Gods,

And, as if he were from heaven, searches the skies.

The idea of an invincible, eternal Ideal,

The god who endures within clayey flesh,

Will rise and rise until he burns his brow.

And when you see him sound the horizon,

Shrugging off old yokes, free from fear,

You will offer him divine Redemption.

-Splendid, radiant in the bosom of endless oceans

You will rise, releasing infinite love across

An expanding universe with an infinite smile.

The World will quiver like an enormous lyre

In the tremblings of an enormous kiss.

-The World thirsts for love: you slake it.

Free and proud, Man lifted his head.

And the first glimmer of original beauty

Shakes the god in the altar of flesh.

Happy with the present good, sad for sufferings past,

Man would sound the depths-would know.

Thought, a mare long stabled though broken,

Leaps from his brow. She must learn Why . . .

Let her leap, let Man find Faith!

-Why this azure silence, this unsoundable space?

Why these gold stars streaming like sand?

Were one to climb the skies

Forever, what would one find?

Does some shepherd guide this great flock

Of worlds, wandering through the horror of space?

And these worlds that the great ether embraces,

Do they tremble at the sound of an eternal voice?

-And Man, can he see? Can he say: I believe?

Is the voice of thought more than a dream?

If man is so recently born, and life is so short,

Where does he spring from? Does he sink

Into the deep seas of Germs, Fetuses, Embryos,

To the bottom of a vast Crucible where

Mother Nature revives him-living thing-

To love amidst roses and to grow with the wheat . . . ?

We cannot know. -Our shoulders bear

A cloak of ignorance and confining chimeras.

Men are monkeys fallen from their mothers' wombs,

Our pale reason hides any answers.

We try to look: -Doubt punishes us.

Doubt, doleful bird, beats us with its wings . . .

-And the horizon flees in perpetual flight . . .

The heavens are wide open! All mysteries are dead

In Man's eye, who stands, crossing his strong arms

Within the endless splendor of nature's bounty.

He sings . . . and the woods with him, and the rivers

Murmur a jubilant song that rises into the light. . . .

-It is Redemption. It is love. It is love.

The splendor of flesh! The splendor of the Ideal!

The renewal of love, a triumphant dawn

When, Gods and Heroes kneeling at their feet,

White Callipyge and little Eros

Blanketed in a snow of roses,

Will lightly touch women and flowers

Blossoming beneath their beautiful feet.

O great Ariadne whose tears water

The shoreline at the sight of Theseus' sail,

White in sun and wind. O sweet virgin

By a single night undone, be silent.

Lysios in his golden chariot embroidered

With black grapes, strolling in the Phrygian fields

Among wanton tigers and russet panthers,

Reddens the moss along blue rivers.

Zeus, the Bull, cradles the naked, childlike body of Europa

Around his neck as she throws a white arm

Around the God's sinewy shoulders, trembling in a wave,

He slowly turns his bottomless stare upon her;

Her pale cheek brushes his brow like a blossom;

Her eyes close; she dies

In a divine kiss; and the murmuring wave's

Golden spume blossoms through her hair.

-Through oleander and lotus

Lovingly glides the great dreaming Swan

Enfolding Leda in the whiteness of his wing;

-And while Cypris, so strangely lovely, passes,

And, arching her richly rounded hips,

Proudly bares her large golden breasts

And her snow white belly embroidered with dark moss,

Hercules-Tamer of Beasts, who as if with a nimbus

Girds his powerful form with a lion skin, his face

Both terrible and kind-heads for the horizon.

In the muted light of the summer moon,

Standing naked and dreaming in the gilded pallor

Staining the heavy wave of her long blue hair,

In the dark clearing where the moss is stung with stars,

The Dryad stares at the silent sky . . .

-White Selene floats her veil

Timidly across the feet of fair Endymion,

And sends him a kiss in a pale beam of light . . .

-The distant Spring weeps in endless ecstasy . . .

Our Nymph, elbow on her urn, dreams

Of the fair white lad her wave had touched.

-A breeze of love passed in the night,

And in the sacred woods, surrounded

By terrible trees, majestic marble forms,

Gods whose brows the Bullfinch makes his nest,

-Gods watch over Man and the unending Earth.

April 29, 1870

Were these poems to find a place in le Parnasse, wouldn't they sing the poet's creed?

I am unknown: so what? Poets are brothers. These verses believe; they love; they hope: that's enough.

Help me, Maître: help me find my footing: I am young: give me your hand . . .

TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Charleville, August 25, 1870

Monsieur,

How lucky you are to be out of Charleville! In all the world, no more moronic, provincial little town exists than my own. I have no illusions about this any more. Because it is next to Mézières-which no one has heard of-because two or three hundred infantrymen wander its streets, my sanctimonious fellow residents gesticulate like Prudhommesque swordsmen, not at all like those under siege in Metz and Strasbourg! How dreadful, retired grocers donning their uniforms! How marvelous, as though that's all it takes, notaries, glaziers, tax inspectors, woodworkers, and all the well-fed bellies, which, rifles held to their hearts, make their shivering show of patriotism at the gates of Mézières; my countrymen unite! I prefer them seated; keep it in your pants, I say.

I'm disoriented, sick, angry, dumb, shocked; I was looking forward to sunbaths, endless walks, rest, travel, adventure, bohemianism, but: I was most looking forward to newspapers, books . . . -Nothing! Nothing! The mail brings nothing new to bookstores; Paris is having a fine time at our expense: not one new book! It's like death! I've been reduced to reading the estimable Courrier des Ardennes, owned, run, directed, edited-in-chief and edited-at-all by A. Pouillard! This newspaper sums up the hopes, dreams, and opinions of the local population; see for yourself! -I've been exiled inside my own country!!!!

Happily, I have your room: -You do recall that you gave me your permission. -I've borrowed half your books! I took Le Diable à Paris. And is there anything more ridiculous than Grandville's drawings? I took Costal l'indien, and La Robe de Nessus, two interesting novels. What else? I read all your books, all; three days ago, I sank as low as Les Epreuves, and then to Les Glaneuses-yes, I went so far as to reread it-but that was it. Nothing more; I've exhausted my lifeline, your library. I found Don Quixote; yesterday, I spent two hours looking at Doré's woodcuts; now I have nothing! I'm sending you some poetry; read it one morning. In the sun, as I wrote it: I hope you aren't a teacher anymore!

It seemed to me that you had wanted to know more of Louisa Siefert when I lent you her most recent poems; I just managed to find some pieces from her first book, Les Rayons perdus, 4th edition. In it I found a very moving and beautiful poem, "Marguerite":

Off to one side, bouncing on my thighs

Was my little cousin with big sweet eyes.

Marguerite is a ravishing girl,

Blonde hair, little lips like pearls

And transparent skin . . .

Marguerite is too young. Were she mine . . .

Had I a child so sweet, blonde and fine . . .

A delicate creature in whom I could be reborn

Pink and guileless with a stare so forlorn

That tears rise to the rims of my eyes

When I think of her bouncing on my thighs.

Never to be mine-an absence I mourn

Because fate, heaping me with scorn,

Delights to see love devoured by flies.

No one will say of me: ah, such a good mother!

No child will look at me and say: mommy!

A chapter unwritten in this heavenly homily

To which every girl hopes to contribute another.

Eighteen, and my life is over.

-I think that's as beautiful as Antigone's laments in Sophocles.

-I have Paul Verlaine's Fêtes galantes, in a pocket edition. Really strange, very funny; but, really, adorable. And sometimes he takes serious license, like:

And the ter

rible tigress

. . . is a line in the book. You should buy a little book of his called La Bonne Chanson: it just came out with Lemerre; I haven't read it; nothing comes here; but more than one newspaper has had good things to say about it;

-So good-bye, send me a 25-page letter-general delivery-and right away!

A. Rimbaud

P.S. -Soon, revelations about the life I'll lead . . . after vacation . . .

Copyright © 2003 by Arthur Rimbaud. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.